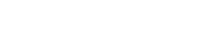

Featured Image from: Brutalismus

Those Look Unfinished

If you’ve ever seen unpainted, concrete buildings that may come off appearing as unfinished, but in reality they already are, then you’re probably looking at Brutalist architecture.

In recent years, it seems like this sort of aesthetic has been on some sort of revival, especially for the interiors of boutiques, coffee shops, or malls. It was the British critic, Reyner Banham, who popularized the term in describing the style that began to trend during the 50s and 60s. However, the term “Brutalism” has always been associated with Le Corbusier, a Swiss-French architect from the 1950s, who first used the words “béton brut” or “raw concrete” in describing the apartments he had constructed in Marseille back in 1952.

In recent years, it seems like this sort of aesthetic has been on some sort of revival, especially for the interiors of boutiques, coffee shops, or malls. It was the British critic, Reyner Banham, who popularized the term in describing the style that began to trend during the 50s and 60s. However, the term “Brutalism” has always been associated with Le Corbusier, a Swiss-French architect from the 1950s, who first used the words “béton brut” or “raw concrete” in describing the apartments he had constructed in Marseille back in 1952.

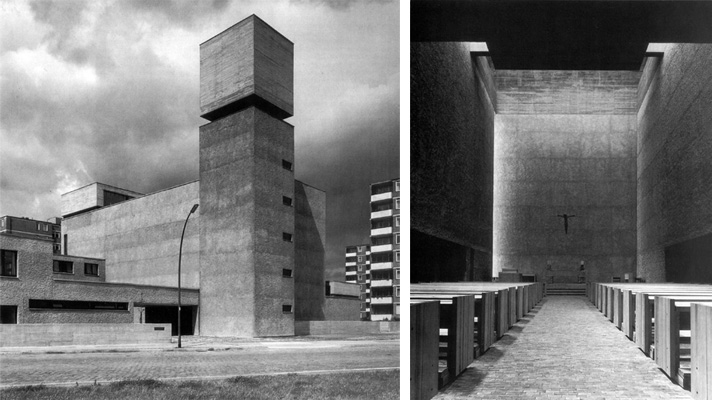

Primarily, the essence of Brutalism lies in the architect’s focus on industrial designs that made the refining of raw materials irrelevant to its function. But to be more specific, there is more to Brutalism than its raw concrete aesthetic.Banham, in an article for The Architectural Review (1955), enumerates three enduring characteristics that make a structure a Brutalist work. These are:

- An image worth remembering

- An undeniable clarity in demonstrating its structure

- An estimation of the materials, given that they bear innate qualities that presuppose their rawness

These elements dictate that the style creates relationships with society through the rawness of its materials. Is it not made obvious that a building’s exterior, such as an archaic and grandiose castle, is an image that can leave a passer-by look back while in transit? It is this image that builds connections, and by displaying the relationship of a building’s structural wholeness, the history of its architecture and era is presented.

Of course, the style did not come without any pushback from critics. Take, for instance, how in the 1960s, the Robin Hood Gardens in London came to represent a different ideal. Designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, the Robin Hood Gardens – a social housing scheme predicated on low-rise blocks surrounding a garden space – came to be completed in the early 70s, thus making it passé, given the socio-economic changes of the times.

Today, the raw aesthetic of Brutalism, which has grown to become synonymous with the deliberateness of an unfinished object, is seen in clothes – from shirts, to jeans, and shoes. Sneakers, for example, have been carrying so much hype since the last decade or so.

Virgil Abloh and The Ten

Virgil Abloh, the artistic director for Louis Vuitton and CEO for Off-White, is the latest purveyor of Brutalism – only that, instead of buildings, he’s been turning sneakers inside out and flaunting their materials. This move isn’t so surprising, especially since Abloh took and finished a master’s degree in Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). Given his many interests such as hip-hop, knowledge in architecture, engineering, and design, as well as his experience in fashion, he started to collaborate with Nike in 2016. The final product is now known as “The Ten” – a collection of ten Nike sneakers redesigned by Abloh. Again, this isn’t so surprising, since he has always loved Michael Jordan, the NBA’s greatest product, and Jordan’s signature line, the Air Jordans.

The Ten, which exemplifies Abloh’s design language, reconstructs the most iconic sneakers ever released by Nike – and this design language is very much Brutalist in nature. The two themes of the collaboration are: “REVEALING” and “GHOSTING.”

The “REVEALING” includes Abloh’s iterations on the Air Jordan I, Air Max 90, Presto, VaporMax, and Blazer Mid. “GHOSTING,” meanwhile, takes on Converse’s Chuck Taylor, the Nike Zoom Fly SP, Air Force 1 Low, React Hyperdunk 2017, and Air Max 97. And by the overarching thematic, the former serves to communicate the hand-made rawness of the respective sneakers’ materials. The latter, on the other hand, intends to showcase translucent materials throughout the second batch of five. What pieces the ten sneakers together is the brashness in displaying the various materials that build these shoes, which is quite essentially Brutalist in nature. In fact, Abloh goes on to state that this release is more than just sneakers, and that it is “larger than design culture,” as he pertains to the shoes’ functionality and aesthetics.

When it comes to the crafting of the collection, all the Ten’s feature either some or all of the following reconstructions: the revealed foam in the tongue, use of quotation marks and bold text, printed labels as if inked on, blatantly exposed stitching, tiny orange tabs, and factory-like zip-tags, and patched-on materials of different makes. There are a handful of recurring visual cues, and these images bind the sneakers together as a collective, which can only fuel the hype. The Ten’s Air Jordan I, for example, can now fetch a price as high as USD 2,777. Sneaker culture has never been this well and booming.

On the Value of Unfinished Objects

Apart from sneakers, we’ve already witnessed how ripped jeans rose to prominence in the past, but in more recent times, the fashion world has seen tattered clothes make a comeback and they’re now calling it “distressed.” While clothes, through constant use, will experience some wear-and-tear, many clothing brands, designers, and fashion houses are coming out with pre-ripped jeans, sweaters, shirts, and blouses to jump on the trend. But really, how different is this from the Brutalist aesthetic of The Ten?

A lot, of course, because the Nike and Off-White collaboration involves the showcasing of its materials – the rawness that Brutalism glorifies as essential in visual communication without compromising purpose. The distressing of clothes, however, may not necessarily make any sense at all, apart from that the ripping and tearing are considered aesthetic. To be frank, one can buy a perfectly sewn plain white shirt and then puncture or burn a few holes here and there to achieve that distressed look. Exposed stitching or tags hanging loose on a hoodie – what does that serve – nothing really significant, right? What it does echo, though, is the bare and unfinished appearance that Brutalism and The Ten exemplifies.

The “beauty” of distressed fashion is not hinged on the deconstruction, but on the destruction – the ageing process, from jacket stains to battered denims, is artificial and this eschews any real functionality. It can be said, however, that they place value on a piece that is made to appear as if it were a work-in-progress. In the highly consumerist society that we live in today, this sentiment comes to make many take a second glance, and evaluate the material world, that whether it is a house, a pair of shoes, or damaged clothes, there remains some value to be held dear. After all, as the old saying goes: “One man’s trash in another man’s treasure.”